Let's Get Lost!

dis·rup·tion

/disˈrəpSH(ə)n/

noun: disruption; plural noun: disruptions

1. disturbance or problems that interrupt an event, activity or process.

Project Details

status : published

typology : visual essay

year : 2020

team : Despoina Papadopoulou, Katerina Examiliotou

publication : informa

Project Publication

As citizens, many of us have become comfortably numb in our private sphere, refusing to interact and relate to others, ignoring our capacity to shape our surroundings, putting to sleep our senses, and forgetting to experience, let alone enjoy our environment. You drive down the road on your way to work. It's a habit. Your eyes are open. How long did it take you to go from one place to another? You walk down the street on your way to the gym. You pass by a couple arguing loudly. You pretend you don't see them. Did you hear what the argument was about?

Our urban awareness is decreased while our senses disassociate from our physical context. We are more often connected to a distant, digital reality, receiving only filtered inputs surrendering ourselves thus to a pre-made choice, a specific way of moving and getting there by a specific route, usually the fastest. No room for surprises. No room for the unexpected. We have already seen where we are going before arriving and by the time we get there we are already transported to the next spot of interest. Always missing the present moment, fearing the unpredictable, never really discovering.

Often dismissed as an unproductive activity, playing is seen as inappropriate and/or meaningless for adults. Yet one could argue that in the same way kids learn how to engage with their physical and social environment through playing, adults could reconnect with it as well. If we think of playing as a disruptor of our reality—in the sense that a game will instantly change our immediate goals, adding rules and requiring a change in the way we perceive and interact with our environment— turning our experience of the urban environment into an game could be the means of reframing our perception of it. Could we add a bit of analogue chaos to our ordered digital realities by bringing back some of the spontaneity, playfulness, and creative curiosity we all experienced once, while we were playing games as children? (de Lange et.al. 2019, 428-434)

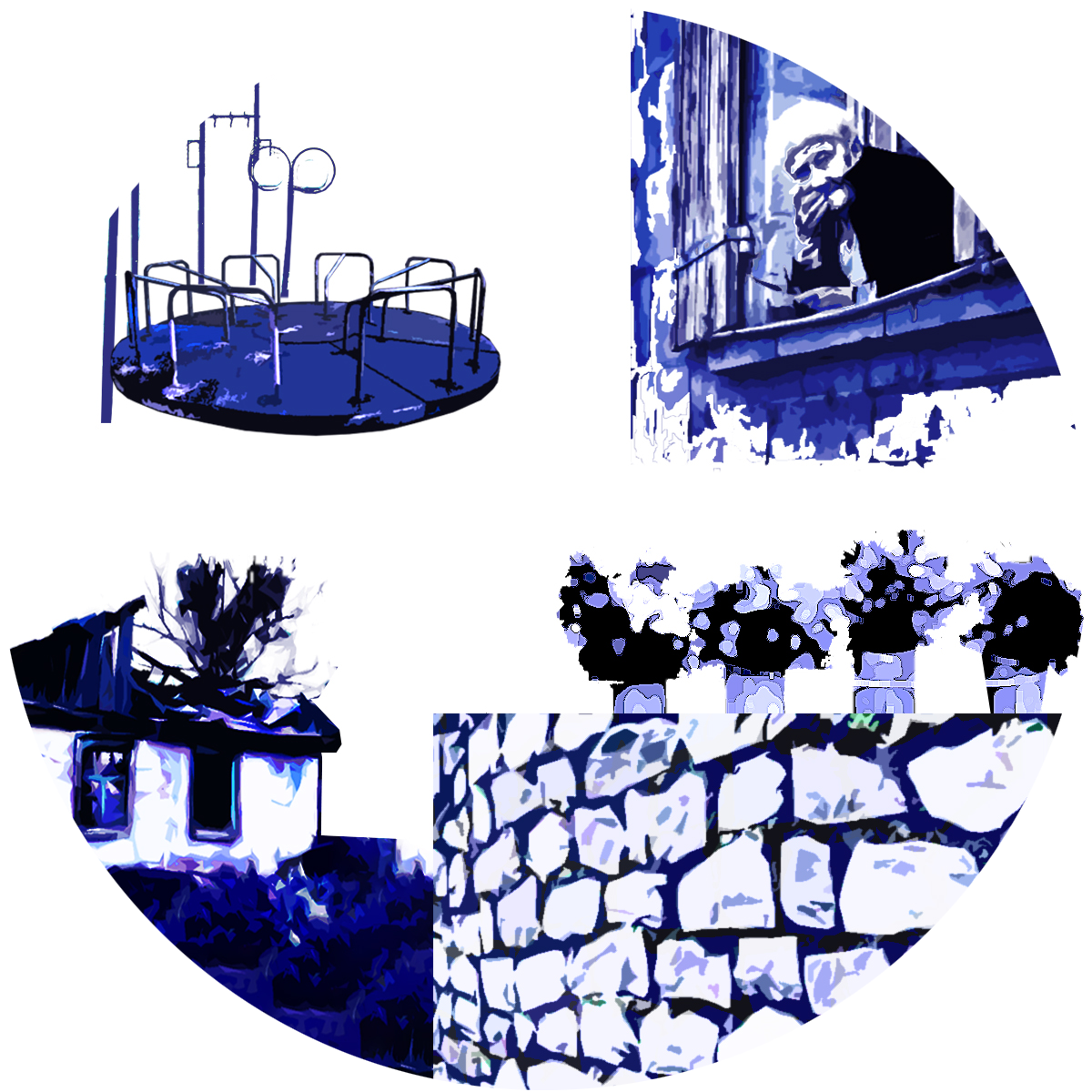

Getting lost was our game and perhaps is relevant in this discussion. We were 7–8 years old when we started playing this spontaneous, outdoor game, invented and directed by us and known only to us— parents couldn’t know. The game was similar to ‘hide and seek’ or ‘treasure hunt’, but we essentially searched for each other . What we found was our own way of experiencing and interacting with our surroundings.

K: It would all start by one of us saying the magic words: Let’s get lost! I don’t remember much from my early childhood but I remember this clearly. Standing back to back with you in the middle of my neighborhood’s playground, counting down to three and starting walking towards opposite directions without looking back. The rules were simple: keep walking forward until eventually we found each other again, ideally in the most remote location in town, in a place yet to be discovered. And to this day I still don’t know if the real goal was to get lost.

D: My earliest memories as a kid also start there: the place where you grew up and I visited eagerly so often. Escaping the confined apartment, throwing myself into the wild, exploring what the out there entailed. It was the place where I was self-indulging in adventures waiting to unfold, in fears to confront, and therefore destined to grow. You, companion and competitor to all our games. And this one was my favorite. The official goal was truly a serious one. Hours would pass with us wandering around thirsty, hungry, and tired but never willing to give up. I couldn’t give up anyway. I would be lost if I did! I had to keep walking until I found you and you could get me back to safety.

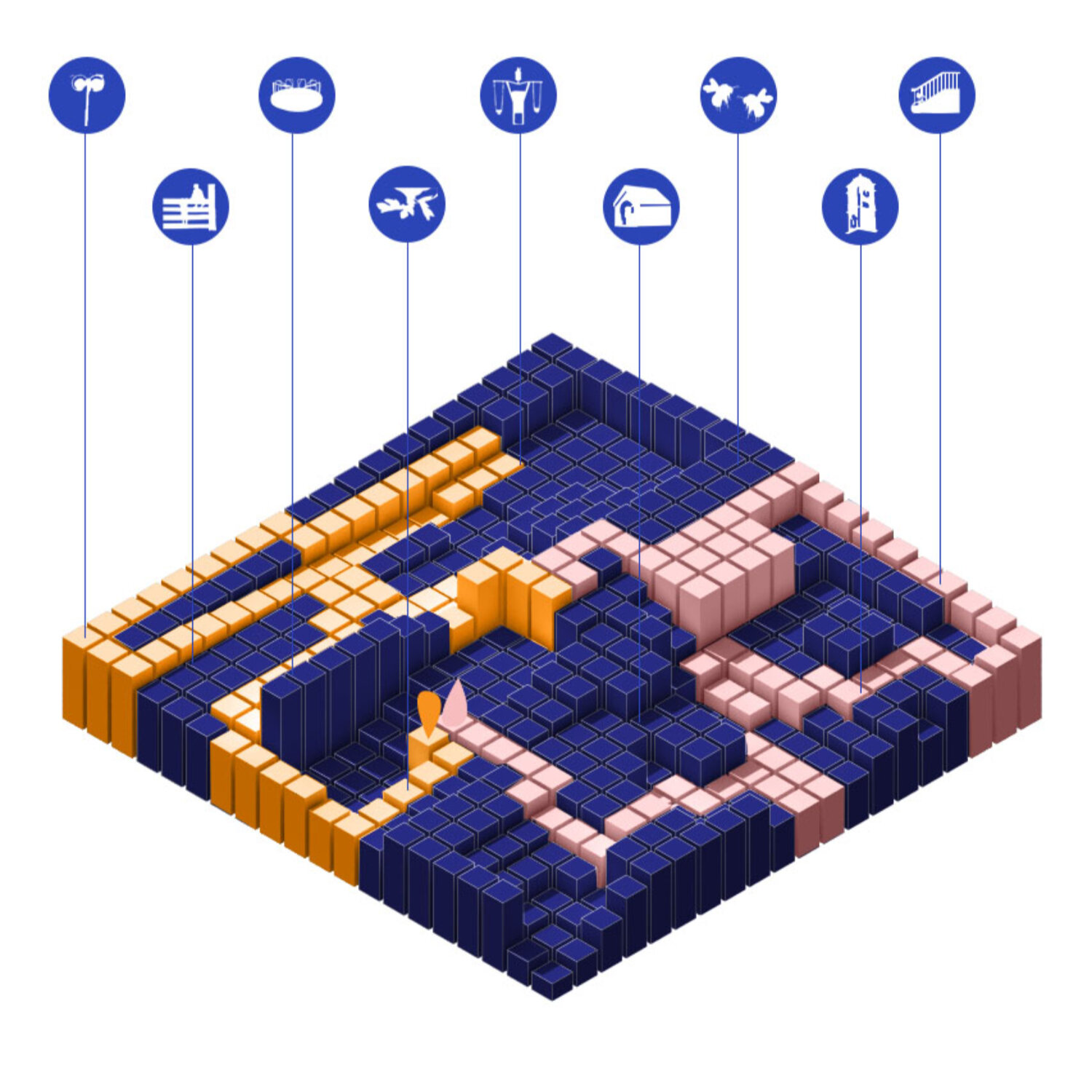

K: Retrospectively, though, us getting lost was much more important than finding each other; we found so much more on the way. We were actively examining our environment, constantly scanning the elements that it’s composed of, searching for things we haven’t seen before to register in our inventory and share with each other. Little urban explorers navigating the short alleys through house fences which seemed like tall fortresses to our eyes. Ready to conquer what was to be conquered and add to the exciting stories we would tell after the game had ended.

D: I thought I was brave; not knowing where the next turn would lead me, not knowing which alley to take, fearful of “danger” approaching with every step. Hidden gardens, abandoned buildings, dead-end paths, old water ponds, laid down fences, strangers passing by; the opportunities for discovery were endless, the possible routes countless, and so were the fears I had to overcome. Fear and curiosity always battled, but the latter always won.

K: I was not brave, I had the advantage of knowing all the places you didn't. I was eager though to turn my everyday world into an unknown one to make sure the game was fair for the both of us. So there were no shortcuts through well-known yards or cheeky turns in hidden alleys for me. Having seen it all with a fresh eye made me recognize and appreciate even the many layers of this well-known and familiar place.

D: We always started our game in this small playground. This bland square with the concrete pavers and a worn-out double swing hanging from a turquoise man-like steel structure with “open arms” that still haunts my nightmares. It looked out of place there, but it somehow anchored us in it and signaled the beginning of our adventure.

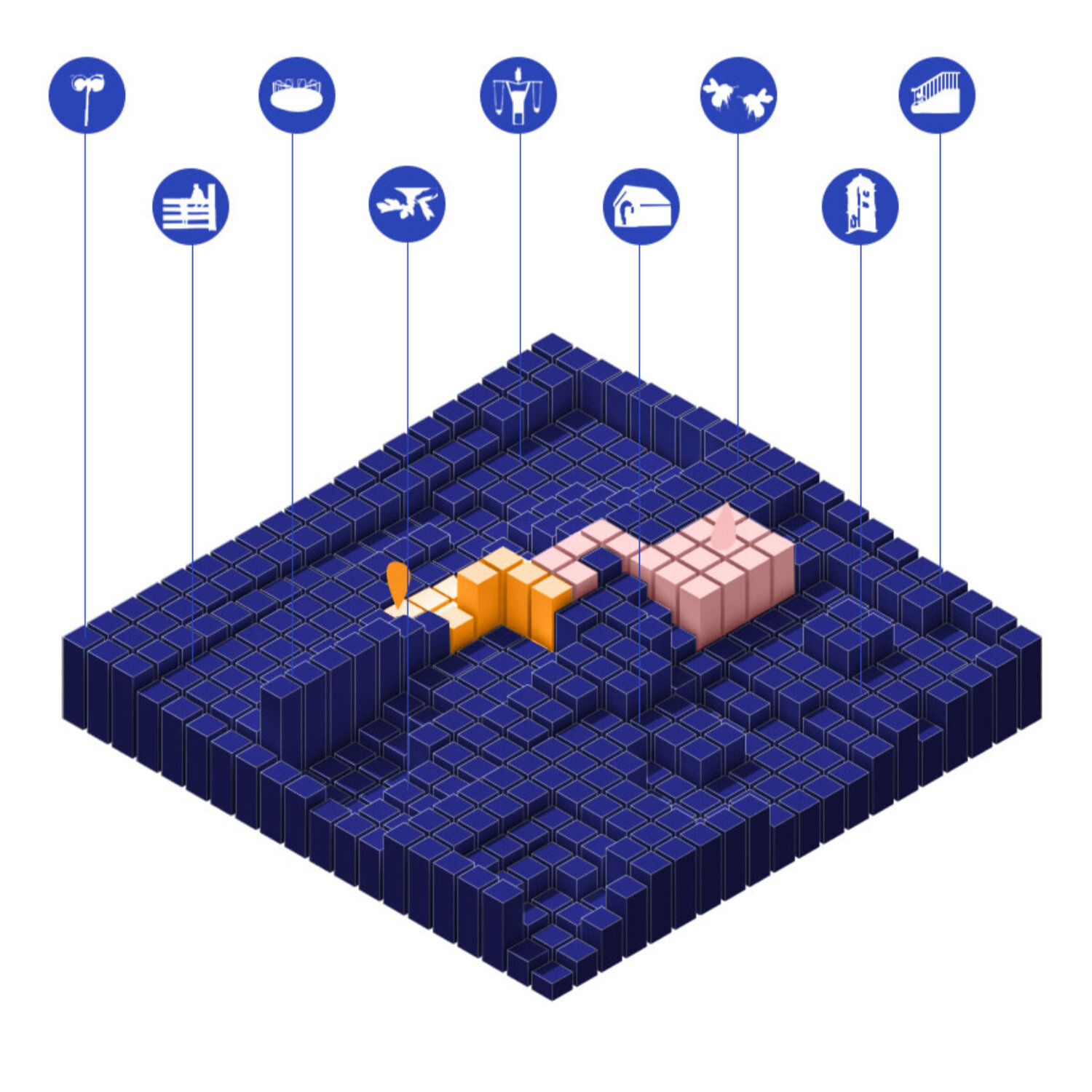

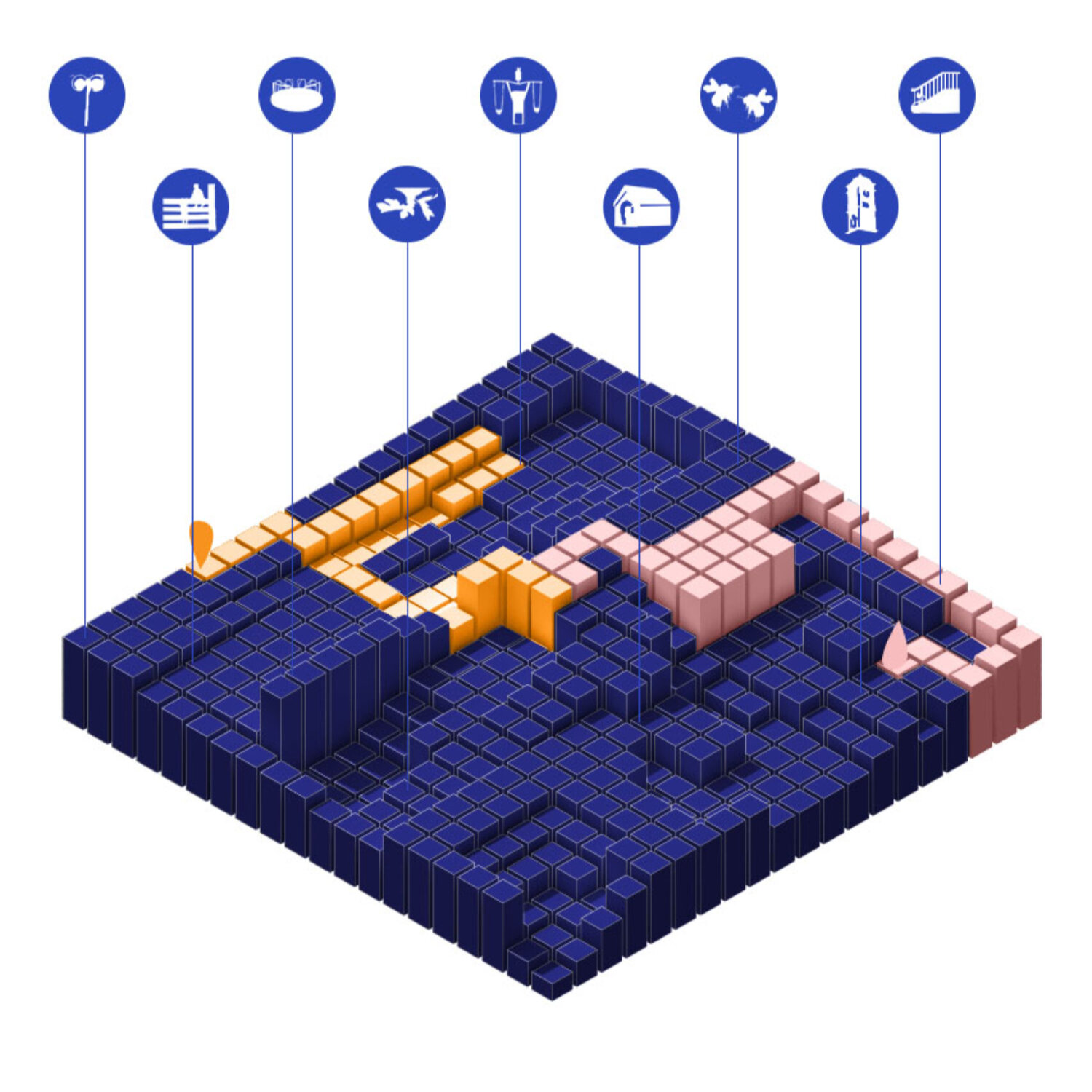

K: After the countdown the ‘game board’ of our adventure would expand from the well-defined playground to the whole town. And with every step and every turn, our personal ‘map’ in this borderless game board would reveal a bit more of the unknown.

D: In this imaginary map-drawing game of ours every time we played each of us would ‘map’ her own journey. These maps were made out of stories we would share with each other after the game was over retracing our steps. Every game was also a shared experience in time and place with a common goal and each experience was unique as our journeys would lead us to new adventures making us want to keep on playing.

K: Sometimes, no matter how much I kept trying to take a turn and find myself at a place I hadn't been before, I couldn’t. Those days, I could only experience part of the game and frustrated I would stop trying to get lost and focus on finding you, calculating my next move, trying to predict where you may have ended up.

D: Sometimes I could see the familiar bell tower of the town’s church but what lay between was a mystery. I wondered which path to take to get there, and which one is safer. In constant fear of confronting barking dogs, I was drawing a map in my mind with possible routes. Those days, after another part of the town had revealed itself to me, and after we had successfully found each other, I walked back home feeling fulfilled and a bit more grown up.

K: I was never scared of the dogs we would find in our way, you know. I was used to them. But I was scared that if you got bored of the game, I would lose my companion.

D: One day I walked past a man who said something to me. Pretending to be a grown up, pretending there was nothing weird in me walking around without my parents, I replied casually and kept going my way. I remember this feeling of pride: I was out there walking by myself, talking to strangers!

K: The narrow streets were usually empty, making me feel like the sole ruler of a place that was all mine, while hoping for no unexpected encounters. It was the fear of strangers challenging my right of wandering alone ‘in places I shouldn’t be in’. It was also the fear that I would have to answer the annoying “where are you going young lady?” and “Nowhere” was not a good enough answer. And to this day I don’t know why not.

D: Luckily, we seem to have maintained the same curiosity, the same lifestyle, really. I think it has to do with this experience we shared, with this game of ours. We still walk slowly and observe the world, feeling a sense of wonder for everything in it. We are not afraid of losing ourselves or each other in it.

K: Why is this game still such a reference point in our lives? Have we romanticized it and used it to explain our personal and professional paths and choices , or could it be that it wired our brains to keep seeking for the unexpected, the unknown, the somehow scary?

D: I feel a strong attachment to the experiences and images gained through this game and to a certain degree I think they are universal for all kids in that age. In some way, all children experience their surroundings through play and those fragments of places stick with them.

K: We , grown ups, we all play less and less, live urban adventures less and less, connect with our fellow playmates less and less, and lose connection to our environment and our social role in it more and more. This is why I'm happy I’ve grown to still act like this wandering fearless child I used to be. Continuing the tradition of walking, exploring, sometimes with you and sometimes alone, seeking for new urban stories to share and people to connect. Never tired of it, and in constant awe with the city around me.

D: And now that I moved to the same city with you, we can play our game again. Picking up from where we left it and perhaps recruiting new members to pass on the message and play getting lost together.